AI’s labor impact, and how to not lose our minds

Welcome to Cautious Optimism, a newsletter on tech, business, and power.

Tuesday! MongoDB reports earnings today. Domestic economic data came in a bit better than expected, but let’s be honest: The market wants Nvidia earnings, and those don’t land until tomorrow. To work! — Alex

📈 Trending Up: Settlement costs … media spine … airplane diplomacy … clarity … carbon removal? … ‘Google Zero’ … Taiwanese war prep … nostalgia in China … what … cheaper eye-care …

📉 Trending Down: Expensive sales teams? … Grok 2 on HuggingFace … Rhode Island energy … free speech … India-US economic ties … EU-US comity … robocalls … the private-sector defense industry …

Things That Matter

Fascism Watch: POTUS is trying to use a claim of impropriety drummed up by his staff to fire Fed Board Governor Lisa Cook. She responded that he has “no authority” to do so, and has lawyered up. Elsewhere, POTUS is vamping about revoking the licenses of two major American news companies. And there are more threats of use of the American legal system as a tool to itch presidential pique.

What xAI claims: Elon Musk’s AI company followed through with its founder’s threat to sue Apple and OpenAI over alleged antitrust violations. The suit — embedded here — makes several notable claims, including that Apple has a smartphone monopoly and OpenAI an AI monopoly in the United States. It’s odd to see a technologist make a claim that I wonder if even Lina Khan would have felt comfortable with, given the existence of Android, Anthropic, and Google’s AI team.

Even more notably, xAI’s claims echo some of the government’s arguments against Google’s search monopoly, including the power of ‘default’ status and how usage can drive more data gathering, which unlocks better product performance, creating an unbreakable loop.

Intel’s warning: The move by the Federal government to demand a 10% stake in American chip concern Intel in exchange for Congressionally approved grants from a few years back is not without risk, the company said in a filing. “The Company’s non-US business may be adversely impacted by the US Government being a significant stockholder,” Intel writes. No shit.

Perplexity’s pitch: AI search startup Perplexity has gotten into trouble with publishers over how it uses their information, and is currently locked in a tiff with Cloudflare over its scraping policies. Yesterday, however, the company introduced a new product — Comet Plus — that offers access to its browser for $5 per month. Existing paid Perplexity users get the service for free, but what’s notable about Comet Plus — Perplexity’s browser is called Comet — is that the startup intends to send 80% of the service’s revenues to publishers. That’s a fat cut. More of this, from more companies, please.

The cynic in me wants to argue that this is a sop to fend of criticism. The optimist in me is excited that an AI company is doing something to support the open web.

AI’s labor impact, and how to not lose our minds

Ed Zitron, an old friend of mine and someone whom I like very much, is currently on a crusade to puncture every inflated AI opinion. Single-handedly. His most recent post, “How To Argue With An AI Booster,” is worth reading even if you are an AI bull. Ed, condensing mightily, thinks that AI capabilities are overblown, AI impact overestimated, and AI zealots annoying.

On the last point, I agree. Ed’s argument about AI’s impact on employment, however, is worth a little prodding.

Where’s Your Ed At argues that while it’s true that “young people are having trouble finding jobs, there is no proof that AI is the reason.” Given the proclivity of folks to claim that, in the near future, all jobs will be done by an AI model or an AI-empowered robot, I get why Ed’s skeptical of the claim. After all, AI has been improving for years now, so where’s the job displacement?

A new paper from Stanford’s Digital Economy Lab sheds a little light.

The study in question leans on data from ADP, a major human resources software and services company. You may have worked for ADP incidentally in the past (it offers PEO services), or are familiar with the company for its regular labor-market data reporting. What matters for our purposes is that ADP is “the largest payroll processing firm in America,” the study notes, providing “ payroll services for firms employing over 25 million workers in the US.” That’s about a sixth of all workers, meaning that the data underlying the Stanford study is as robust as we could hope for when leaning on a single source of information.

So, what did the researchers find? Here’s a rundown of their key claims:

AI is starting to have an impact on early-career workers in professions that are AI-exposed: The paper found “substantial declines in employment for early-career workers (ages 22-25) in occupations most exposed to AI, such as software developers and customer service representatives.”

There’s a junior/senior split forming amongst AI-exposed jobs: The paper notes that while “overall employment continues to grow robustly [employment] growth for young workers in particular has been stagnant since late 2022. In jobs less exposed to

AI[,] young workers have experienced comparable employment growth to older workers. In contrast, workers aged 22 to 25 have experienced a 6% decline in employment from late 2022 to July 2025 in the most AI-exposed occupations, compared to a 6-9% increase for older workers.”

AI-applicability doesn’t necessarily presage early-career job reductions: The paper reports that “not all uses of AI are associated with declines in employment,” with “entry-level employment [declining] in applications of AI that automate work, but not those that most augment it.”

To sum: In careers where current-day AI is pertinent and used to automate instead of augment, early career jobs appear to be impacted by AI. (See page fourteen for more detail on the automate/augment split.)

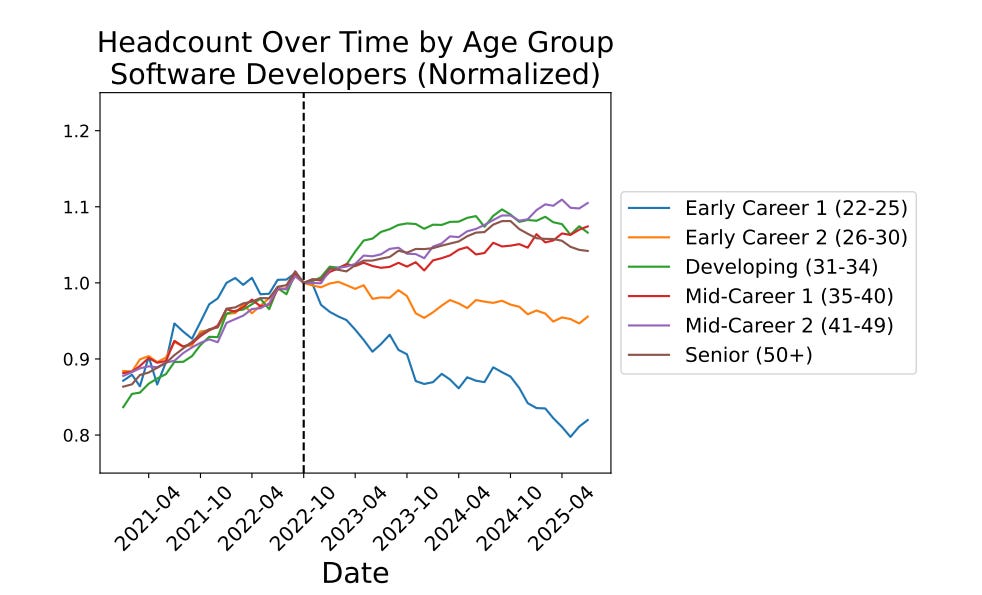

The changes the paper outlines are clearer in chart form. Here’s an employment chart for software developers, broken down into age cohorts, normalized to a value of one for October 2022. (ChatGPT came out the next month, kicking off the current genAI boom):

Early-career software developers are facing a changed labor market in that before the advent of ChatGPT, coders enjoyed similar employment gains regardless of age. Since ChatGPT’s release, the youngest developers are seeing their gigs evaporate.

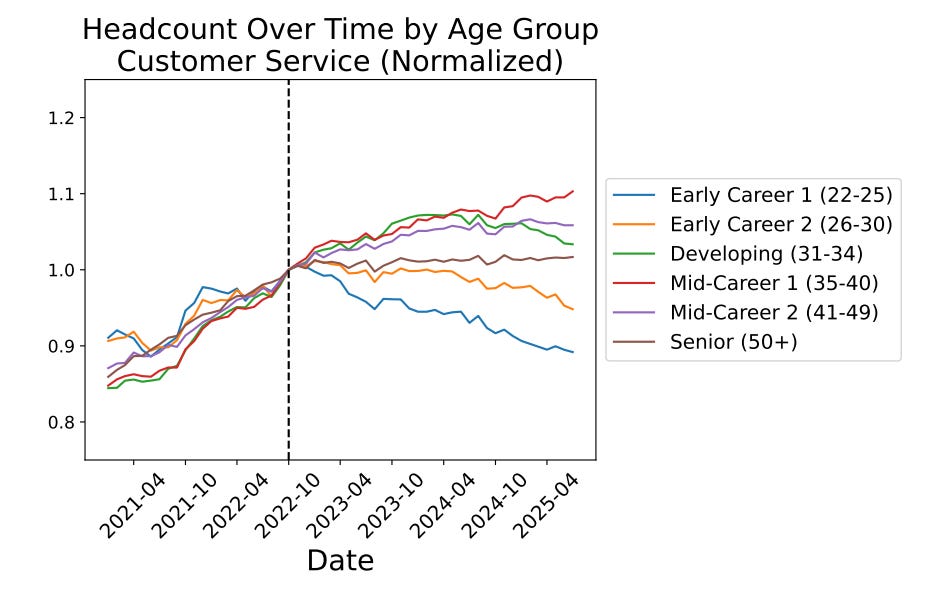

Another industry where I see lots of startups building AI-empowered tools to replace human workers is customer service. Here’s a chart of those roles, per ADP data, normalized in the same fashion:

The data here is slightly less sharp a curve and more striated across age bands, but pretty clear in trend terms.

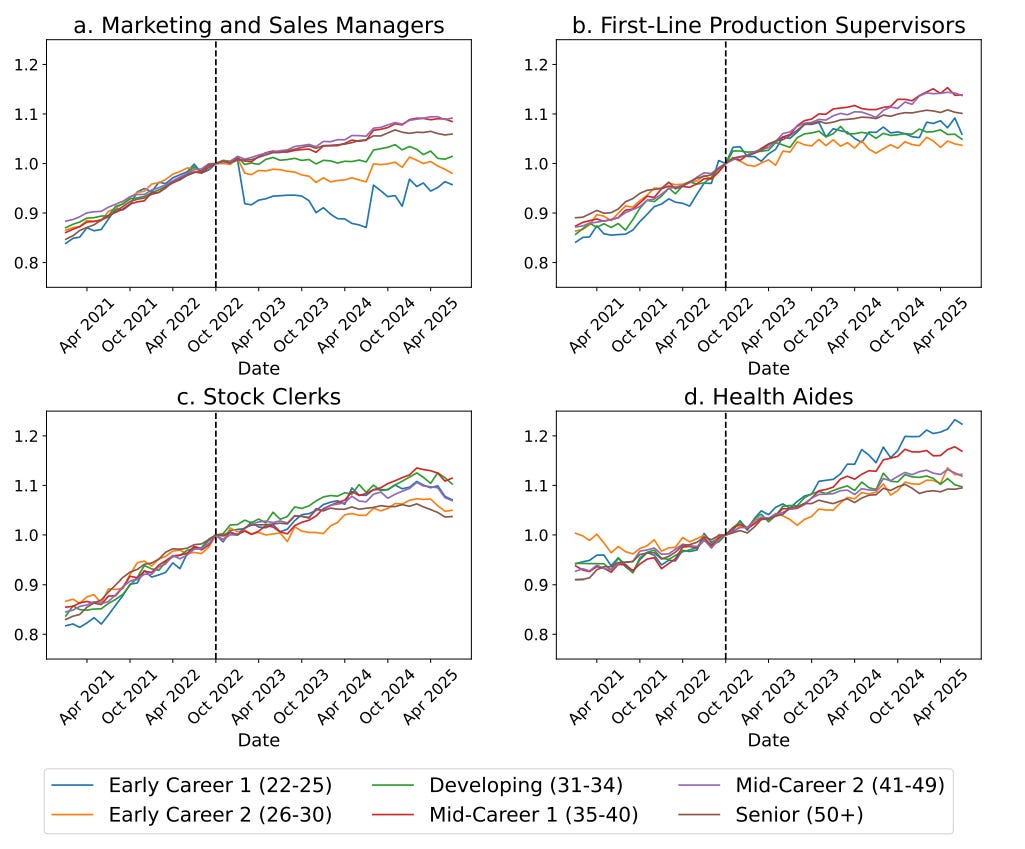

Yes, but do gigs that are less AI-exposed show a similar curve? No. From the same paper, here’s four different professions (normalized again to October of 2022). The top-left chart is for a job that the paper rates as AI-exposed, while the other three are not:

Back to Ed’s point about some AI folks being annoying. Yes, the bloviation is incredibly annoying. It plays well on X, a social network that decided to dumpster itself by paying users for engagement, incentivizing the worst sort of viral dreck. But we shouldn’t let our annoyance at the threadbois — did I do that correctly? — dissaude us from what reasonable data shows.

Frankly, the paper better matches the anecdotal information I’ve collected than either the doomers (AI is about to take all our jobs) or the doubters (AI isn’t about to take your job). If you read the nursing subreddit, you find a very different labor picture than what forms in your head after reading early-career computer science message boards. In one, there’s agitation for higher pay, and a willingness to take management to task over labor disputes. Amongst younger programmers, it’s tales of mass rejections, intricate interviewing tracks, and regular, persistent layoffs.

I think the question we should hold onto, instead of asking whether or not AI is coming for at least some jobs now, and probably more over time, but instead to gist out which industries could be next on the disruption timeline.

Back in July, we took a look at just that question. Microsoft Research came up with a list of jobs that are the best fit for AI (“occupations with the highest AI applicability score”) and those that were the worst. Amongst the roles with the most risk? Sales reps, customer service workers, and several programming-ish jobs (“data scientists,” “web developers”).

That tracks. So, what does the data say could be in danger as AI improves and works to break out of technology-mediated work? Translators are probably cooked; writing is going to be replaced with AI schlock; some machining work will get even more computer-controlled; you get the idea. It’s a mixed bag.

Which means that we should expect to see age-cohorted job displacement in roles where worker experience accretes with time; and non-age-cohorted job displacement in roles where worker experience has an upper bound, or is less impactful. You can fill in which side of that split your industry sits, and then by remembering your age, you can sort out how much at risk — or not — you are today.

AI isn’t going to replace everyone by late 2026. But I think we have enough data now to say that for some early-career workers, AI-empowered employment reductions are real and should not be dismissed.