The Big Short dude is worried about Big Tech earnings

Also: Time to bring the $100M ARR Club back!

Welcome to Cautious Optimism, a newsletter on tech, business and power.

The Big Short dude is worried about Big Tech earnings

Investor Michael Burry, famous for his bets against the housing market before the Great Recession, thinks that big tech companies are obscuring the cost of their massive data center investments.

Burry’s argument, that tech companies are stretching depreciation schedules too far, implies that tech companies’ near-term performance is being overstated, giving investors an incorrect view of how profitable the hyperscaler and neocloud set truly are.

What’s the argument? Simplified:

Tech companies buy lots of gear, recording those costs in their cash flow statements by deducting capital expenditures (capex) from operating cash flow to report free cash flow (FC).

Tech companies depreciate capex investments over time against a set schedule that they share with investors.

Tech companies record depreciation against earnings as it accrues.

Example: If Hyperscaler_X spent $10 billion on data center one year and had a five-year depreciation schedule for those assets, it would record a $10 billion hit to its free cash flow in the first year, and $2 billion worth of yearly depreciation costs that impact earnings per year for a half decade. (There’s more to it than this, including how depreciation impacts operating cash flow, but let’s not get too nitty.)

The longer an asset lasts, the less it costs in yearly contra-profit terms; a $1 billion asset that depreciates on a 100-year time frame costs 10% as much per year in profit impact as a $1 billion asset that depreciates over 10.

Therefore, companies changing how long they expect assets to retain value can push the profit impact of historical capex out, spreading it over a longer period of time. In this way, the conversion of capex into negative EPS is less painful in the near-term.

So what? Burry notes that tech companies’ moves in recent years to extend asset depreciation schedules mean that data center capex is being counted against earnings more slowly.

This is fine as long as the assets in question last as long as the hyperscalers and neoclouds believe they will.

Burry, however, thinks that “massively ramping capex through purchase of Nvidia chips/servers on a 2-3 yr product cycle should not result in the extension of useful lives of compute equipment.”

The investor calculates that hyperscalers using — in his view — too generous capex depreciation schedules for AI compute gear will boost their earnings by $176 billion.

Alright. Got all that? Good. Now, is Burry right?

Maybe a little, but probably not enough to cause an earthquake. There’s some reporting that fully-utilized GPUs may last just one to three years, but that information is pretty tenuous. It is true that if you take a GPU and use it at max capacity, it will fail more quickly than a GPU in a gaming PC that is only used a few hours each day.

If GPUs and related chips (TPUs from Google, Trainium chips from Amazon, etc) were failing at a quick clip, major tech companies would need to change their depreciation schedules to account for their shorter-than-expected useful lives.

We’ve seen that, actually. Amazon changed its server life expectancy (depreciation schedule) from six years to five years earlier this year (emphasis ours):

We completed our most recent servers and networking equipment useful life study in Q4 2024, and are changing the useful lives of a subset of our servers and networking equipment, effective January 1, 2025, from six years to five years. […] The accelerated depreciation will continue into 2025 and decrease operating income by approximately $0.6 billion in 2025. These two changes above are due to an increased pace of technology development, particularly in the area of artificial intelligence and machine learning.

Today, every hyperscaler expects between five and six years worth of use from their current gear. That’s up from four to five years in 2021. Given the sheer amount of money being spent on capex today by the largest cloud providers, the longer life expectancy of their gear does help with profitability right now.

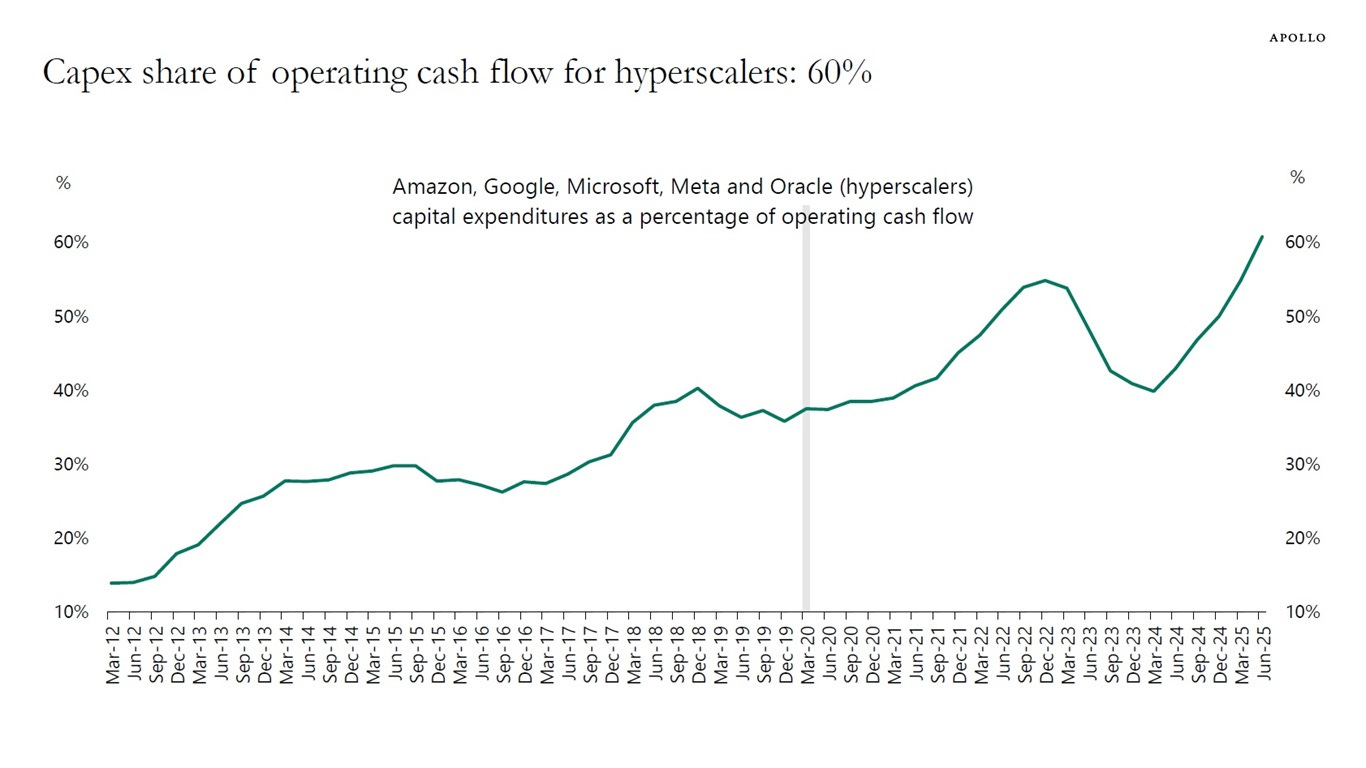

Especially when so much of cash flow is going into capex today amongst the cloud giants:

Should we trust the companies? There’s evidence that Google’s TPUs are lasting a very long time, with eight-year-old gear still generating revenue. And CoreWeave recently noted that it managed to re-up an H100 contract within 5% of the value of the first term of the deal, implying that even last-gen AI chips are still in high enough demand to keep generating profitable revenue (as discussed yesterday).

Long-lasting gear and durable profitability from those chips is hardly what we’d expect to see if Burry was painfully correct.

Still, Burry is a legend. Which other hedge fund denizen got the Big Short treatment? But that doesn’t mean he’s always right; no one is. I agree wholeheartedly that there is risk in today’s capex ramp, but even if every single hyperscaler had to lop a year off their depreciation schedules for data center gear, I don’t think the direction of AI investment would change. Sure, there would be some valuation erosion, but the stock market is around all-time highs right now.

A final wrinkle: There’s more and more debt showing up in the data center game, often predicated on the value of the underlying GPUs purchased for those facilities. If you want to worry, ask yourself what will happen to those loans if AI demand fails to meet expectations, or expensive Nvidia chips start failing en masse. That could get bloody.

Time to bring the $100M ARR Club back!

I used to write a series about startups reaching the $100 million annual recurring revenue milestone for TechCrunch (here, and here). I eventually retired the collection because it became repetitive, but I think it’s time to reprise the effort.

Why? Because I am starting to lose track of the number of private companies that are reaching the nine-figure threshold. Back in the day, getting your top-line to $100 million meant you were ready to go public. Today, the IPO Mendoza Line is closer to $400 or $500 million, making the $100 million mark more of a dividing line between startup and unicorn, or startup and private-market giant. Pick your favorite term.

But the list of private companies (startups) that have reached $100 million in annual recurring, or annualized, revenue is insanely long. We’re not just talking about Lovable:

Gamma: Reached $100 million ARR, per its recent funding round announcement in November 2025.

Customer.io: Recorded $100 million ARR, shared by the company in October 2025.

HeyGen: Got to $100 million ARR in October 2025, up from $1 million in April 2023.

Govini: Grew to $100 million ARR in October 2025, shared while announcing a $150 million round.

ElevenLabs: Reached $200 million ARR in September 2025, announced at the same time as an employee tender.

Cohere: Crossed the $100 million ARR mark around August 2025, per one of its investors.

Harvey: Recorded $100 million ARR in August 2025.

Replit: Crossed the $100 million ARR mark in June 2025, up from $10 million at the end of 2024.

Synthesia: Reached $100 million ARR in April 2025, announced in conjunction with fresh capital from Adobe Ventures.

Perplexity: Reached $100 million ARR in March 2025, stating at the time that its product was under-monetized.

dbt Labs: Crossed $100 million ARR in February 2025, claiming that it had also secured more than 5,000 customers at the same time.

Brave: Crossed the $100 million annualized revenue mark in the first quarter of 2025.

That’s just most of the public nine-figure revenue milestones announced this year. We could expand the list by looking at 2024, too, but at some point, we’ll start chewing the fat.

When people worry about the AI bubble, the list above is my mental rejoinder. Sure, some spending will go to zero, but the insanely quick revenue growth and resulting scale of many startups today is a bulwark against TVPI annihilation. That should help you sleep soundly at night.