Uber’s AWS era

And: Flywheels, y’all. They’re real.

Welcome to Cautious Optimism, a newsletter on tech, business, and power.

Monday! Over the weekend, the world digested US participation in airstrikes against Iran. Asian stocks mostly fell, as did shares in Europe over concerns of a wider, more intense conflict, the chance of higher oil prices, and potential maritime trade disruptions. Crypto prices also fell, so everyone is having a poor start to the week. Onward! — Alex

📈 Trending Up: Small mercies … humor … IP … robotaxi competition … the Big Three … billion-dollar buys … Chinese robots … Spanish-NATO relations … Russian airstrikes on Ukraine … debt relief in Africa …

📉 Trending Down: Vibes … prior authorizations … startup team size … AI music? … food aid …

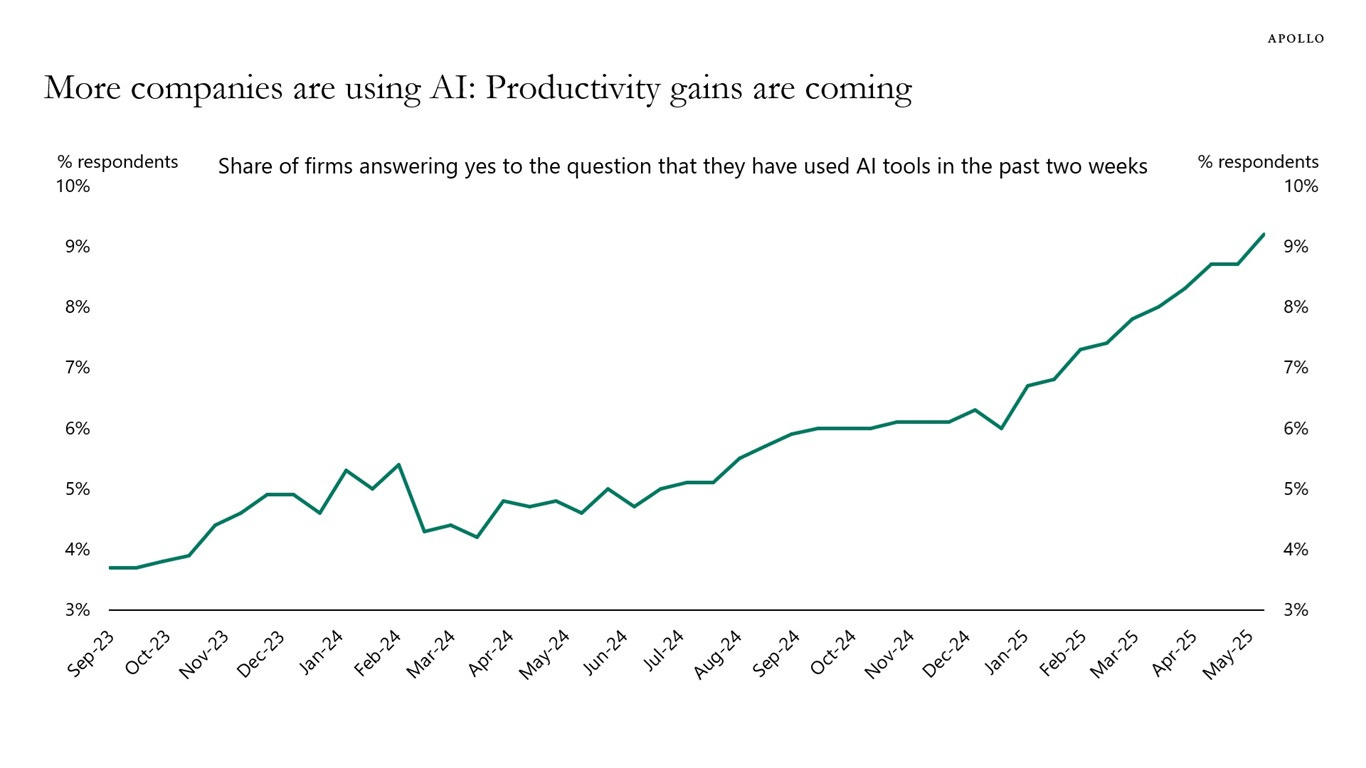

📊 Chart of the Day: From Apollo’s chief economist, indication that AI usage amongst the 1.2 million firms it surveys has reached a grand total of 9%. That’s up around 50% from 6% at the start of the year. Lots, and lots of adoption remains ahead of us. And if you are in the genAI tooling provides at least some productivity gains, then this is good news for national GDP growth.

Much ado about Zohran

I do not live in New York City. You might, as 14% of subscribers to this newsletter hail from the state. But no matter where you call home, you’ve heard about the upcoming NYC mayoral primary election.

There are two candidates of note: Andrew Cuomo (former governor), and Zohran Mamdani (current State Assembly member). Despite name-recognition, lots of spend, and notable endorsements, Cuomo is trailing Mamdani for the first time.

Not by much, and the Clinton nod came only recently, so the race is incredibly tight. Why do we care? Because Mamdani is very unpopular amongst the people that this newsletter regularly covers. For example, NYC denizen Logan Bartlett — a managing director at Redpoint — responded to a chart showing Mamdami as the favorite to the win the Democratic nomination for mayor with one word: “Idiots.”

Now I like Bartlett, so let’s give his viewpoint some credit:

Mamdani’s platform for housing abundance is stupid: Freezing rent-controlled housing prices doesn’t bolster supply, and his plan to build 200,000 “permanently affordable, union-built, rent-stabilized homes” over ten years is far from sufficient. The Mamani view is that allowing the market to create more housing through rezoning has failed. So, enter the state. Having lived in a city where housing was hard to build, and calls to build more ‘affordable’ housing had precisely no impact, and in an era where we can see the power of truly rapid free-market construction, Mamdani’s policies on housing are about as welcome in my house as anti-nuclear policies.

Paying taxes sucks: Mamdani wants to raise the state’s corporate tax rate, and apply a new flat tax of 2% on earners of $1 million or more. While I have never spied Bartlett’s personal taxes, I presume that he and his company are currently paying the highest state rates, and thus would not enjoy having less income after paying their taxes.

Mamdani has some good ideas, including protecting our queer brothers and sisters, family-friendly policies that could help combat the city’s sub-replacement total fertility rate, not using cops for social work, and chatter about making it “faster, easier, and cheaper to start and run a business in New York City.” But oof, his economic views.

What should we make of the Mamdani surge? Simply that if the city’s wealthier deciles wanted a candidate for mayor that was more friendly to their own viewpoints, perhaps a better champion could have been secured than Andrew Cuomo. Hell, even the VCs agree with me.

Uber’s AWS era

Uber has matured into a cash machine. The company’s $42.8 billion worth of Q1 platform spend (+14%) converted into revenues worth $11.5 billion (+14%), leading to $1.8 billion worth of net income and free cash flow of $2.3 billion.

But while Uber is best known today for its marketplace businesses that connect gig workers for human, and food-delivery tasks to consumer demand, the company is also fomenting software dreams.

Uber’s Uber AI Solutions had a limited rollout under a different brand name a few years back, but this month the ride-hailing giant greatly expanded its AI services to reach some 30 markets, and include access to humans for annotation, translation, and other AI tasks; pre-built and custom AI datasets for training; help with agentic AI systems; and the same “platforms Uber uses to manage large-scale annotation projects and validate AI outputs” that Uber itself uses.

The way I see it, Uber is taking a chunk of the internal technology it built for itself and making it commercially available externally. Amazon did something very similar with AWS, and that experiment changed the world.

Uber’s AI offerings won’t move the revenue needle for the company for some time. But potentially high-margin software revenue is never unwelcome, and investors might sniff out some future cash flows from the work that could help Uber defend, or even extend its current share price.

There are other examples of tech companies breaking out some of their internal work for external consumption. You could put all of Meta’s quasi-open source AI models under the same aegis. Or Google’s open-sourcing of some of its own core technologies like it did with Blaze back in 2015. Notably by making Blaze — a tool for automating software builds — open-source under the Bazel name, startups like BuildBuddy were formed.

I used to rag on companies that were more tech-enabled than pure technology plays. All the costs of a technology company, but without the gross margins the argument went. Well, here’s one way to stuff that derision right back in my face.

Got another example? Hit reply to this email and let me know what you know.

Cursor(y) projections

Much like yourself, I spent a portion of the weekend thinking about Cursor’s growth rate. Something I am not sure of is how large the market is for Cursor and its competitors.

You could do some simple math to get a loose TAM figure:

BLS data indicates that there were 1.53 million “software developers” in the United States in 2022, not taking into account “computer systems analysts,” “QA workers,” “network architects” and other similar, related roles. With more time passing — and thus more CS grads — and an expansive view of the market let’s say there are 3 million software folks in the market today that might use Cursor or a competing service.

Picking a $40 average price point — somewhere between Cursor’s lowest and higher price points — you could infer that in time we’ll see code-helping tools bring in $1.44 billion worth of top-line.

Clearly, that number is too low as the dollar amount earned by Cursor, Windsurf, and GitHub Copilot is already getting close. Cursor at $500 million ARR, Windsurf at somewhere between $50 and $100 million ARR, and GitHub’s own Copilot revenues estimated at $300 million or more earlier this year — so there’s a lot more demand than our early calculation implied.

Another error in thinking is to presume that if we could count the entire developer count in the United States today we could accurately guess the TAM for Cursor et al. Instead, products like Cursor and friends are going to greatly expand the number of folks in the United States slinging code. A bit like how Uber made the taxi market larger, coding assistants are going to assist new coders.

So, I am zero-percent worried about Cursor’s ability to keep growing. The more it grows, the more capital it has access to; the more capital, the more the company can invest in improving its service; the better Cursor gets, the more folks it can empower to build stuff; those people will give Cursor money. Flywheels, y’all. They’re real.