Wealthfront is going public! Hell yeah

And a defense of quarterly earnings 😤

Welcome to Cautious Optimism, a newsletter on tech, business, and power.

Tuesday. While folks fret about overcapacity for AI compute workloads, OpenAI and Meta are signing up for even more GPU supply from CoreWeave. OpenAI I somewhat understand — the company needs to secure compute capacity ahead of its own fleet of owned/led data centers are up and running. But Meta? It’s spending $66 billion to $72 billion this year on capital expenditures; that’s not enough?

Alright, enough AI mastication. To work! — Alex

📈 Trending Up: Punishment for fraud … ‘Tesla time’ … gambling … robotic deliveries … shutting down the government … AI regulation … Daniel Ek’s time atop Spotify … The Dispatch … Indian employment … Chinese support for the German far-right …

There was once a push by nearly every social service to add stories to their platform; even LinkedIn got in on the fun. Now, short-form video is the flavor of the year, so companies as far afield as DoorDash are getting into the game. Ew.

📉 Trending Down: Internet access in Afghanistan … Cerebras’s IPO timing … the Gaza peace deal? … AI costs … economic activity per the Dallas Fed?

Things That Matter

In defense of quarterly earnings: There’s a push afoot to limit the pace of regular corporate earnings disclosures to twice-yearly instead of quarterly. This is a mistake. POTUS claims that we must move to less frequent reporting because China thinks in decades. Apart from the weirdness of his phrasing, it’s worth noting that companies listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges report quarterly.

Even more, companies like Nvidia, Alphabet, Microsoft, Apple, and Amazon all rose to global prominence while reporting quarterly. Hell, the most interesting companies actually report more frequently than four times per year. Robinhood drops monthly trading data. Tesla pre-announces car delivery figures.

Perhaps if we were in a moment in which technological change was slow, investment modest, and the rules of capitalism (trade, tariffs, taxes, geopolitical jockeying) were static, less frequent reporting might make sense. But we’re in a period of accelerated technological advancement (AI, green energy, fusion, self-driving cars, robotics, etc), breakneck investment (Mag7 capex), and jarring shifts in the structure of global capitalism all at once. This is the time for more information from companies, not less.

Google bends the knee: While we wait to see if Microsoft will fold and allow the White House to determine whom it can and cannot hire, Google’s YouTube division just paid POTUS $24.5 million for yanking his account ages ago. YouTube is paying the President for using its own protected rights as a company.

It’s hard to read the choice as anything other than a bribe. Or an extorted fee. Pay up, or suffer. Now, Sundar Pichai is helping fund the White House ballroom of all things, while showing the current administration that Section 230 protections aren’t; instead, corporate America is telling the President that it is more doormat than counterbalance.

Shame. Shame. Shame.

AI model companies attack the app layer: OpenAI wants to help sell you stuff. It also wants to build a social app, and is cooking up a “start of day” experience. Both OpenAI and Anthropic have built coding tools that compete with offerings from startups. Anthropic also recently showed off a vibe-coding like service. The majors are encroaching on work traditionally — I know, I know — left to smaller startups. Perhaps the moves will generate M&A. Or a string of dead, smaller companies in their wake.

For investors with cash in both model companies and startups building atop those models, it’s going to get awkward.

Wealthfront is going public!

Hell yeah. Here’s the filing.

After several years in the doldrums, venture-backed IPOs are driving a rising tally of liquidity for private-market investors. While 2025 is proving more fecund than the preceding fallow years, we remain far from 2021’s IPO proceeds and pace today.

Wealthfront is working to make 2025’s exit market shine brighter, however, underscoring how well fintech debuts have performed this year. Would we see a listing from the roboadvisor if Circle hadn’t gone first? If eToro hadn’t pulled the trigger? Or Chime? Or Klarna?

While new money is chasing AI bets, older wagers on financial technology are finally coming good. Wealthfront first raised known capital in 2008. It closed its final venture round in 2018 when it raised $75 million. Now, in 2025, it’s ready to go public.

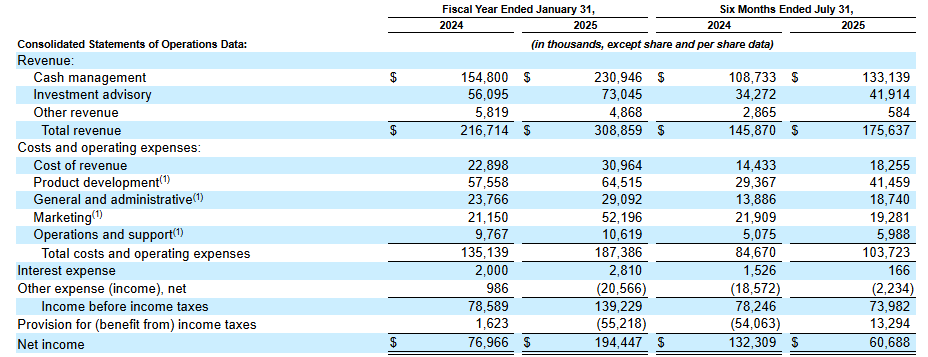

As you might expect from a company that has self-funded for the better part of a decade, Wealthfront is profitable. Not adjusted profitable; straight up making money. Here’s the income statement:

Running the numbers for you, Wealthfront grew 42% from its fiscal 2024 through its fiscal 2025, and 20% from ~H1 calendar 2024 to ~H1 calendar 2025. Despite slower growth, with a net margin of 35% the company’s loose Rule of 40 score is north of 50. That’s a spotlight on excellence, frankly.

Note that while the company’s GAAP profitability declined in its most recent two quarters compared to year-ago tallies, Wealtfront recorded a huge tax benefit in the first half of 2024. Not because it became so much less profitable over the same timeframe.

Wealthfront is best known for its place in the robo-advising wars, a time in which it and Betterment (and, later, Acorns and M1 Finance) fought for consumer deposits and investment portfolios. It seems quaint in retrospect given the rise of Robinhood, but there was a time when Wealthfront was one hot startup.

So hot that UBS nearly bought it back in 2022 for $1.4 billion; that deal fell apart but the Swiss financial giant did invest $70 million into the startup at the former deal price (via a convertible note). A tender offer may have pushed its value up to $2 billion in 2024. So, Wealthfront is a unicorn IPO. Those are always worth celebrating given the size of today’s unicorn value backlog.

Tell me about the business

Of course. Wealthfront makes money in two ways.

First, by sending user cash to partner banks (its ‘cash sweep program’). Partner banks pay Wealthfront for providing deposits, and Wealthfront keeps a chunk of the resulting revenue, remitting the rest to its users. Regarding its ‘cash management’ service:

A portion of the gross amount [from partner banks] is paid to our clients as interest by the program bank for the program deposits, and we receive the remainder as our fee for the cash management services that we deliver to our clients. We set the rate clients receive and therefore the portion of the gross amount paid to our clients is determined by us.

Interest rates are falling today, but are far above ZIRP levels, meaning that there’s more revenue from holding cash today than there was a few years back. (I wrote about this phenomenon extensively for TechCrunch back in 2023.) So, as total cash on hand at Wealthfront has risen, its revenues have also scaled.

Second, Wealthfront makes money by charging 0.25% “less fee waivers, of assets held in client accounts.” As Wealthfront’s revenues are sensitive to assets under management, its rising total asset base (“Platform Assets”) has allowed it to grow: