Why xAI's revenue could be a key indicator of the AI bubble

Welcome to Cautious Optimism, a newsletter on tech, business and power.

Monday! Fed Chair Jerome Powell is under attack by POTUS for not lowering interest rates as quickly as the President desires. Everyone thinks that attacking central bank independence is a bad idea, and yet, here we are.

Elsewhere, we’re watching ICE riot and Trump claim to be the head of Venezuela. Also, we might dissolve NATO (?) to steal Greenland (?) from Denmark (?) our ally (?).

But let’s turn to economics, where POTUS intends to call (?) for a 10% cap (?) on revolving consumer credit lines because the credit providers are ripping off consumers? Such a move would collapse credit availability in the nation and cripple airlines, and is so stupid an idea that even Bill Ackman said something about it before deleting the tweet and donating to the person who killed Renee Nicole Good.

Finally, a co-founder of Palantir seems not to think much about women as a group (he also retweeted this).

Now that we have all that out of our system, let’s get to work! — Alex

📈 Trending Up: The chattering class … Democrats in Alaska? … GOP spine … political ass-kissing in tech … Grok investigations … BitGo’s IPO … defense startups in the EU … a free Iran? …

📉 Trending Down: Making friends in media … Google referrals to publishers … driving to get stuff … labor’s share of GDP …

Things That Matter

xAI’s surprisingly small footprint: American AI lab xAI’s revenue doubled in the third quarter to $107 million from Q2, which is impressive for just three months. Though, we should note that xAI is growing from a much smaller base than its key rivals.

Anthropic added around 8,000 million dollars worth of annual run rate to its accounts last year, while OpenAI added as much as 14,500 million dollars of annualized revenue in 2025.

What’s notable is that with Anthropic at a $9-$10 billion revenue run rate, and OpenAI theoretically at around $20 billion, the two companies sport pretty manageable revenue multiples (measured against their current valuations of $350 billion and $500 billion, respectively). Paying 35x for Anthropic shares or 25x for OpenAI shares, seems reasonable, which is why both will raise more capital at a higher price this year.

Enter xAI, which touts a valuation of about $230 billion — about 537.4x its Q3 2025 run-rate revenue. If we presume the company doubles revenue again next quarter, it’ll still be worth just 268x run-rate revenue. Investors seem to be betting that xAI’s efforts to lead the AI pack will soon unlock incredible revenue growth. With that in mind, xAI’s top-line growth curve is probably one of the key indicators of a bubble out there today.

If xAI can grow into its valuation in 2026, AI investors would not overshoot the target. But if the company struggles to reach run-rate revenue in the billions this year, they would have loaded for bear (wrote big checks) when they were in fact hunting squirrels (to a company without sufficient prospects).

AI labs want to read your MRI: On the heels of OpenAI rolling out a version of ChatGPT for consumer health queries alongside tools for the medical world, Anthropic has launched Claude for Healthcare, a “set of tools and resources that allow healthcare providers, payers, and consumers to use Claude for medical purposes through HIPAA-ready products.”

Speaking of intra-AI competition:

OpenAI scores a PR win over Anthropic: While global nerds went weak at the knees over Claude Code, its maker recently clipped the agentic coding service’s wings.

After folks discovered that they could port their personal Claude Code accounts to third-party tools and consume Anthropic compute outside of the mothership or having to pay API credits, Dario et al slammed the door.

Anthropic probably thought: Why would we let customers take our crown jewel elsewhere? And, why would we subsidize a potential competitor?

So what did OpenAI do? Doubled down on its own coding tool Codex, and decided to prioritize “working with open source coding agents and tools to support them in the same way as OpenCode, so that Codex users can benefit from their account and usage in those combined with using our models in [C]odex directly.”

So far, this looks like a marketing win. If OpenAI manages to pull folks from Claude Code to Codex, then it will be a business win, too.

Shopify is the Amazon of the future: Shopping on Amazon is a pretty miserable experience today. The search is a messy, over-engineered slop-and-advertising fest, it’s hard to tell who is selling what, and shipping times are uneven. We all still use Amazon, but I wonder if its aging e-commerce bones are starting to thin.

That’s why the company’s rejection of third-party agentic commerce interactions is interesting. You may sympathize with Amazon, but while the company is circling its wagons, Google has built a new “open standard for agentic commerce” that it calls “the Universal Commerce Protocol,” or UCP for short.

OpenAI also launched a competing standard last September.

Shopify says it helped Google create UCP, which is “open by default, so platforms and agents can use UCP to start transacting with any merchant.” What’s more, the partnership allows Shopify merchants to “sell in Google AI Mode and the Gemini app, powered by UCP.”

Open and forward-looking? I’d bet on that over whatever Amazon is busy trying to squeeze another basis point of advertising revenue out of.

A wealth tax twist

The citizen petition in California that would levy a one-time tax on the state’s billionaires is causing a ruckus. Since we last checked in, billionaires have been working overtime to get their assets out of the state just in case the bill passes.

Given that California Governor Gavin Newsom opposes the wealth tax, I was surprised to see so much vitriol aimed at the state’s elected leaders. It turns out that Rep. Ro Khanna endorsed the taxation mechanism, so a bunch of intra-state wealth is gearing up to try to rip him from office.

Most importantly, a bit of arcane language has taken the spotlight. From Section 5303 of the 2026 Billionaire Tax Act:

For any interests that confer voting or other direct control rights, the percentage of the business entity owned by the taxpayer shall be presumed to be not less than the taxpayer's percentage of the overall voting or other direct control rights.

Tech folks are reading the quote thusly: Shareholders in companies whose equity grants them outsized votes compared to their equity position will be taxed as if they owned as many shares as their voting rights indicate.

Confused? Let me help, but recall that we’re speaking generally and loosely here:

A company with a single class of shares treats all its shareholders the same. If you own 10% of the shares, you get 10% of the votes.

Therefore, a founder who owned 10% of her company could face the Tax Act’s charge for 10% of its value.

A company with multiple classes of shares may not treat all its shareholders the same. For example, a founder could own 10% of the shares in their company, but control 70% of the voting rights if their shares afforded them several votes per share.

Because our theoretical founder controls most of the votes, the Act will presume that their ownership is commensurate with their voting power. Therefore, you could get taxed on a sum greater than what you own based on what you control.

Cheeky.

In the current era of Silicon Valley, it’s not unusual to constrain voting rights to a small set of insiders. Founders retaining voting control of companies is not rare, and it’s even popularly espoused that founders should retain complete control of their companies in perpetuity. So there are many founders in the market today who set up their cap tables to ensure control, and they may now be taxed as if they owned a lot more stock than they really do.

Not a good idea. Sure, I’m a little skeptical of incredibly centralized voting control in companies, but I don’t think that charging someone for the full value of their startup simply because they have voting control is fair. At a minimum, it’s not a practical idea, as it could bankrupt a host of founders. It’s also too clever by half.

Just as it appears that New York City denizens are staying put despite Mamdani’s victory, I don’t think any single move could shake Silicon Valley’s perch in California. But one could certainly put in motion its decline from global prominence into something weaker and less impressive.

A fun question: If you took half of Silicon Valley from California and sprinkled it over Miami and Austin, would the US tech industry become stronger or weaker?

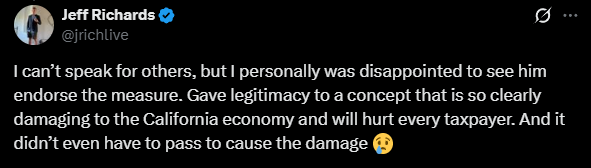

Notable Capital’s Jeff Richards, one of my favorite venture capitalists, helped explain why so many folks in California are mad at their local politicians when the Tax Act is a citizen-led push:

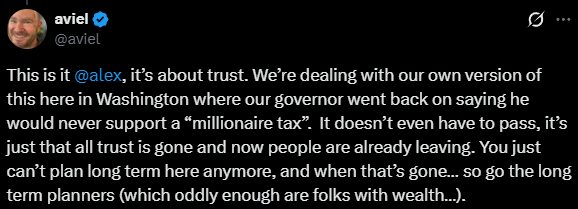

What damage? Capital is effectively fleeing the state. Founder and investor Aviel Ginzburg weighed in, too, adding:

For the rest of us mere mortals, the tax code is pretty kind. The Federal estate exemption allows for a couple to pass $30 million to their children without penalties, for example. And you get to stop paying Social Security taxes after your income reaches $184,500.

But that’s chump change compared to the paper (and real) wealth being generated in the technology industry today. With startups growing faster than ever and valuations creeping higher, a lot of founders (and investors!) are today worth a mountain of money.

Given that the wealth in question is broadly tied to the country’s economic vitality, it doesn’t bother me too much. Sure, I think it would be the bee’s knees if founders and venture capitalists expanded employee option pools so that the wealth was more broadly shared inside of startups, but that’s a quibble.

But considering how mobile the wealthy can get, and how hungry lower-tax states are to welcome them, you can’t make your tax code as punitive as the Tax Act wants, and not see people leave. As we wrote earlier:

The 2026 Billionaire Tax Act would prove a boon to Florida, Texas, and other states with tax codes more friendly to the wealthy than California. Put another way, lower tax rates in other states create a soft cap on how much California can ask of its own citizens; too much and they’ll decamp.

This is doubly true if we’re reading the Tax Act’s treatment of multi-class shareholdings correctly. Oof.